We could see only as far as the headlights reached into the darkness as we drove over the ridge and into the wadi bed. We thought it would be dry, but as our guide opened his door he slipped out into a swirling black hole of water, taking with him a wave heavy with our belongings, shoes and – most importantly – my doll. We drifted sideways down the river, waist deep in water, as my father assessed the situation, telling us that we weren’t moving very fast while he tried to steer. I was four years old.

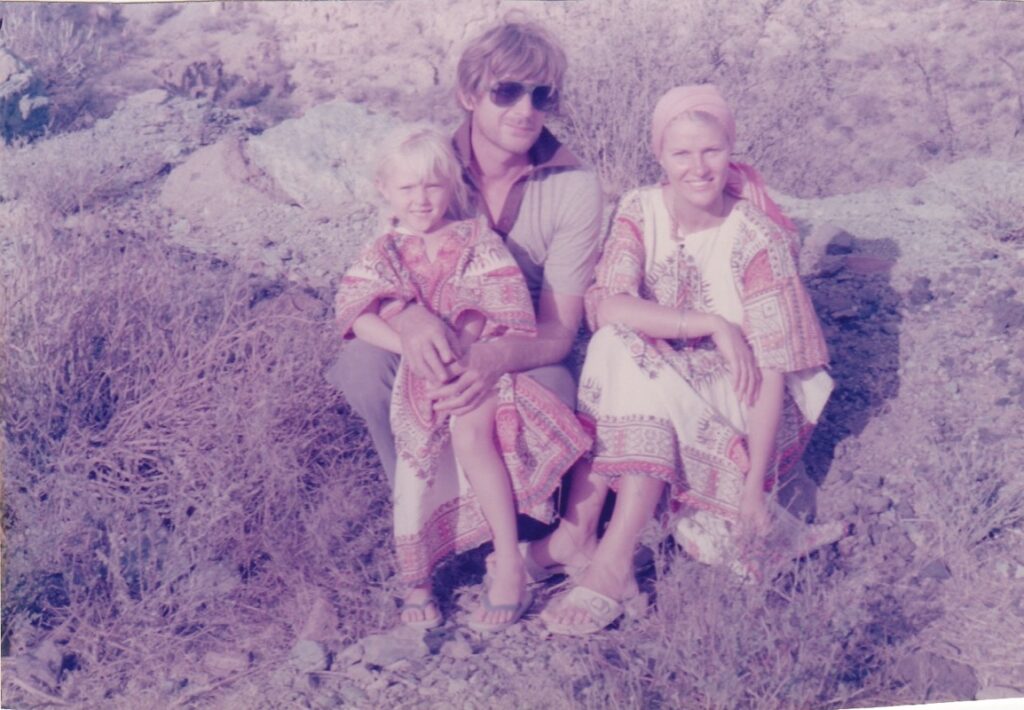

In the summer of 1975, my parents drove from Larne, Northern Ireland to Sana’a, Yemen following a map drawn on the back of a cigarette packet. The journey took the best part of seven weeks – I don’t remember much, except for the star-roofed souks of Damascus and driving though the deserts and mountains of Saudi in convoy with six huge Pakistani trucks. Sometimes we ate with them, my mother and I sitting to one side of a circle of men. We parted company along the Christian highway (bypassing Mecca) as we continued onwards to Yemen.

This wasn’t the first time we’d travelled like this. When I was 18 months old, we travelled by boat from Southampton to Nigeria – but, of course, I was too young to remember that journey. This was my first memory of our many adventures overseas as a family, and of a childhood of travel. And Yemen will forever hold a special place in my heart.

On friends and family

Sana’a was to be our home for two years. We lived in a nice villa with an L-shaped garden brimming with huge pomegranate trees, and a night watchman, which was essential at the time.

Previously, north Yemen had been under Ottoman control and south Yemen a British Protectorate, but in 1967 the British finally withdrew from the south. The two sides officially became separate countries, with the south adopting a communist government – the only Arab country in the world to do so. With over 400 tribes in the region wanting power or aid, there were always tribal disagreements and a possibility of a dangerous incident – hence the need of a night watchman.

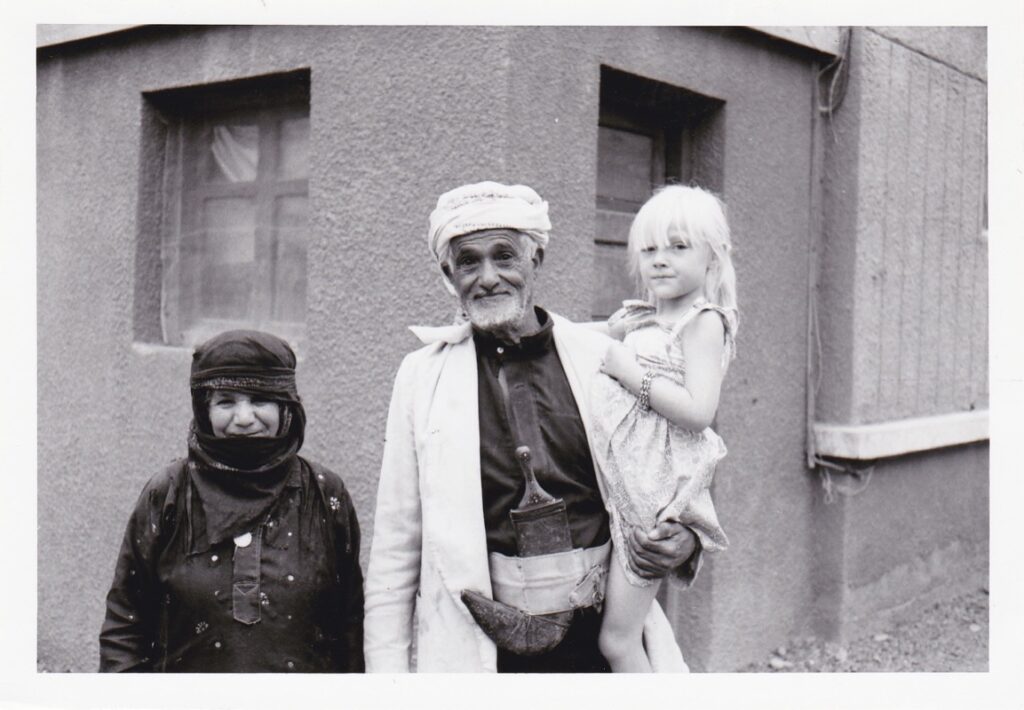

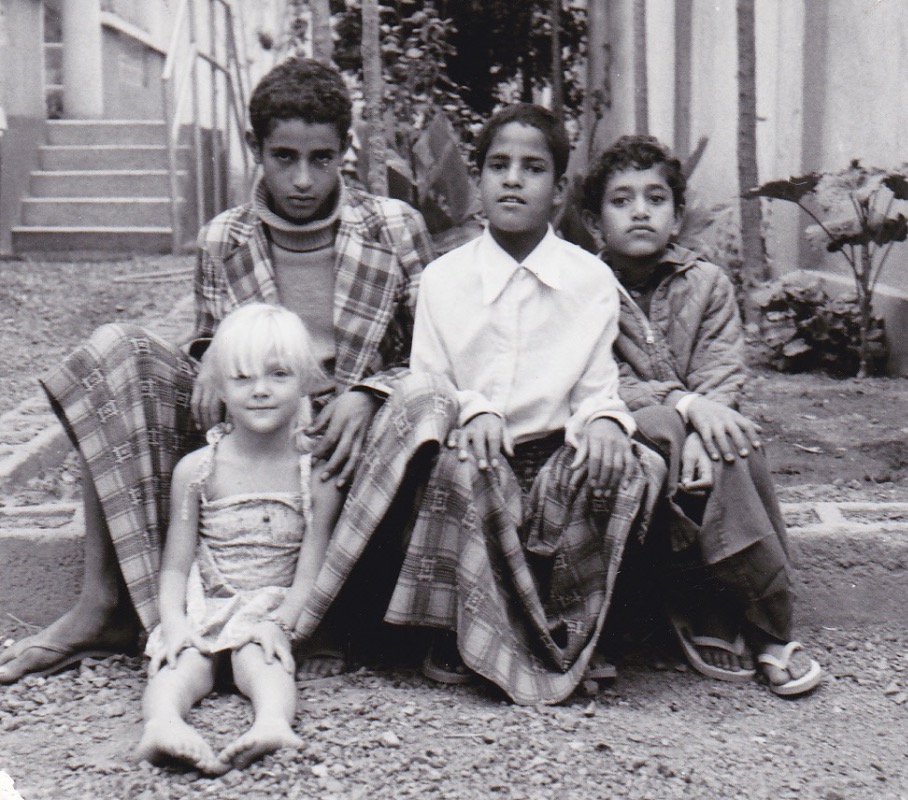

Nasser lived in a small house attached to ours with his wife Ditta, daughter Khairiyah, and her nine-year-old son, Nabil, who was to become one of my closest companions. I used to love hearing him knock on our back door and shout ‘Taal!’ (come!) when the cartoons were on – they had a TV in their house, but we didn’t.

I’d go out and sit with the family, eating from huge plates of rice and meat, often with potatoes and spice. (Khairiyah loved to use fenugreek in pretty much everything). I’d watch Scooby-Doo in Arabic or some black-and-white puppet show, and as a result my Arabic became quite good. There was laughter and cuddles and Khairiyah used to play with my hair. Sometimes we would sit on the back steps and chat while our cats (Caesar and Bubbles) prowled around.

One particular weekend we went to Nasser’s home village in Bani Hushaysh, 25km east of Sana’a. Nabil and I were thrown into the boot of the Range Rover with some cushions – this was the ’70s after all, not really the era of health and safety – and we tumbled around happily with every bump and bend in the road. The rest of the family were squeezed into the back seat like badly packed assorted vegetables – different shapes and sizes all competing for space.

We made the trip so my father and his friend Rudi could fix the family’s well, but I also think Nasser wanted to show us his home and a different side to life in Yemen – not the city, but the farms and the villages. This area is famous for its grapes: huge deep purple orbs of juiciness. He had a wonderful stone house with a donkey and fantastic vineyards, and before long we all had wet chins as we gorged ourselves on grapes sitting under the canopy as the warm dry breeze came up the valley.

Nabil’s cousins, wearing brocade hoods, watched us like suspicious birds, worried perhaps that we might eat the whole crop. We laid the grapes out in the sun to be dried into fat raisins, and came home laden with bags full of the sweet, flattened discs.

On Sana’a

I recall the tight alleyways of Sana’a’s old town: the houses all leaning on each other and skyscrapers made from mud with coloured windows and painted doorways. Cars and bikes used to whizz by, and little shutter doors would open showing a tiny shop with a person almost embedded within, selling knives, nuts, cloth and wheelbarrows ofqat (khat). This mild narcotic plant is popular with Yemenis, who stuff it into one cheek and hold it there, letting the juices slip down their throats. As a child I thought they looked like hamster people.

They weren’t the only animals I remember – the meat market had goat heads hanging over the shop fronts, their tongues sticking out in a gruesome warning with flies dancing on their lashes. In fact, flies followed you everywhere… and children followed me, hoping to touch my blonde hair. Often people stopped my father to ask, ‘Why have you dyed her hair the colour of an old lady?’

The streets were always busy with people. Women would walk together, their hair covered with huge multicoloured clothes, and some girls wore hoods buttoned under their chins. The Tihamah ladies were distinguished by their high conical woven hats that perched precariously and provided shade and an area of cooler air above their heads. Men wore futas, lengths of material a bit like a sarong, folded around and tied at the waist usually with a belt, and an ornate curved dagger placed at the navel.

The beautiful mosques and mud skyscrapers of Sana’a © Kirsten-Hamilton Sturdy

When the mosque calls started, it was one of the most amazing sounds – a haunting domino effect. One mosque would start, and then another and another and before long, the whole of Sana’a seemed to sing out, voices spiralling between the mud houses and out across the mountains. It was almost like the sound would bounce around and fold back on itself… comforting and emotional, like waves on a beach moving backwards and forwards, pulling you in. It still brings tears to my eyes when I think about it.

On animals

During Ramadan we had sheep in the garden – they lived here for a month or so to be fattened up, munching complacently on the grass. That’s if you could call them sheep – they looked more like a caricature, the sheep that you imagine from the Bible with fat shaggy tails and skinny necks. We would eat them during the Eid celebration, and the next day their skins would be hanging up on the washing line like towels. I don’t ever remember being upset by this – to four-year-old me it seemed perfectly normal.

I had a pet guinea pig while we lived in Sana’a, but it started killing his babies (which is apparently quite common), so we gave him to Nasser to eat. Sure enough, the next day the little skin was on the washing line. My mother thought she could make a pair of gloves from it, until an eagle swooped down and snatched it away. It must have been very disappointed with its catch.

On holidays

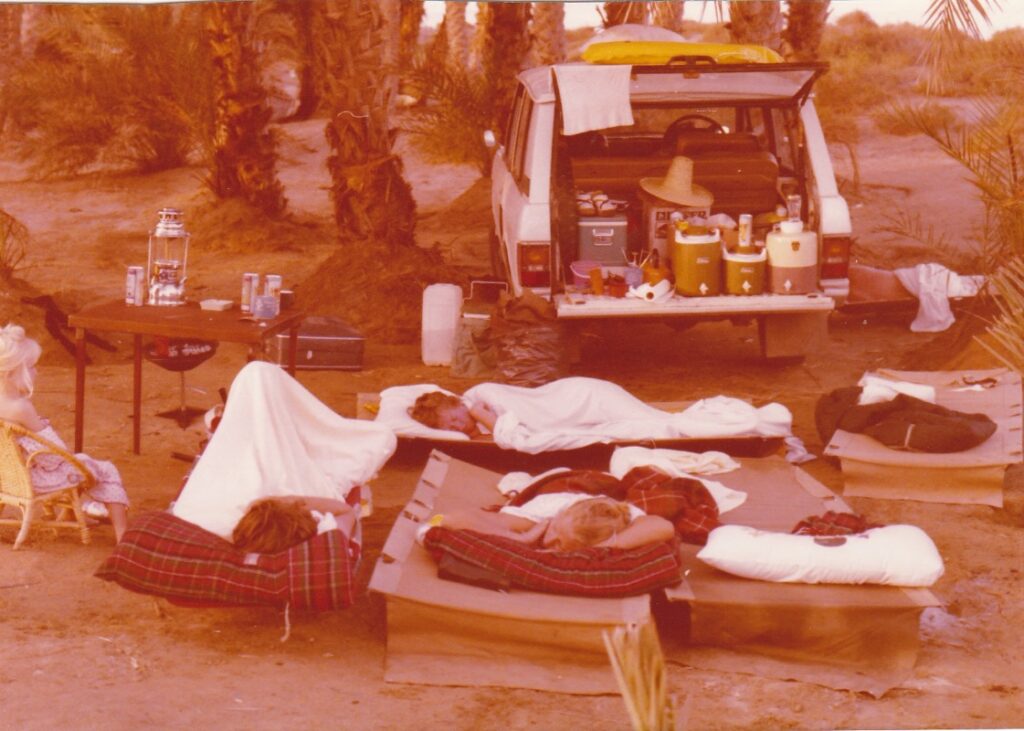

A favourite place for us to visit and camp was Hokka (also spelt Al Khawkhah), situated on the Red Sea Coast about 200km southwest of Sana’a. I loved our camping trips – we’d drive down from the heights of the capital (which sits at about 2,250m) and wind our way past the terraces to the coast. Yemen has some of the most extensive terrace-farming systems in the world due to the steepness of the mountains and poor soil quality, but I remember thinking the fields looked like green ribbons hugging the slopes.

Down on the coast, the sand was so deep that half the fun was to see who would get stuck. Sadly, that was rarely us – our Range Rover was too strong for the sand and my dad loved rally driving. I remember one time we pretty much dragged our friends’ Volkswagen Beetle – handle- deep in sand! – to the beach.

For me, Hokka was a great place to visit as a child, as I was free to roam and play among the palm trees. Occasionally fishermen or villagers would venture out to speak to us, usually women and children. They were bewildered by my boy doll as it came complete with working parts – the kind that needed its nappy changed. My father didn’t know the Arabic word for doll so, to my tears and their horror, he decided to kick it to show that it wasn’t a real child.

We would sleep out under the stars, so bright and clear as there were no towns or light pollution to block their rays. I remember once being woken at about 2am, taken out of my bed and carried in my white nightdress down to the water’s edge.

A few of my parents’ friends were there, splashing about wildly and flapping their arms, making butterfly wings as the water dripped off them. To me, it looked electric – blues and greens flickered off their skin and sequins of water tumbled down their bodies. They danced and swirled around in the shallows and with every kick the water sparkled. I was totally mystified and a little scared to join in, so I sat on the beach and watched the colours. Of course, it was just bioluminescence – the chemical reaction that releases light energy from marine plankton – but magical nonetheless.

On memories

Flashes along the synapses of my mind bring up other images that play like a few seconds of a film: cutting down a pine tree in a huge forest for Christmas; washing our fruit and vegetables with sterilising tablets; dust hanging like fat golden spheres in the evening air through my window. I remember it being so hot that the tarmac would bubble and melt – one time I lost my favourite clogs in a sticky mess. I can also recall the moment I met explorer Freya Stark, who to me was just an old woman in a floppy hat!

Memories are the fragile threads that connect us to the past, and of course as a child, I saw all this as a magical land of frosted gingerbread houses and slightly dust-covered, friendly people. I was happy within a Yemeni family and my parents never showed any fear or worry. But, unbeknown to me, it was a time of tribal wars. Every male wore a jambiya (a curved dagger) and most carried a Kalashnikov or some type of old rifle. It was commonplace for foreigners to be ‘kidnapped’ by tribes and used as ransom to the authorities to get medicine or a working well in their village. The government would relent and the hostage would be released (after being very well looked after), but as soon as the hostage was freed, the government would blow up the well or stop access to medicine. It was an ongoing situation of desperation.

Despite this, Yemen holds a wonderful dear memory for my family. And one day I hope to return and see Khairiyah and Nabil and say As- salamu alaykum… I have missed you.

Born in Northern Ireland, Kirsten Hamilton-Sturdy spent most of her childhood years in other countries, including Nigeria, Libya and Bangladesh. She’s since been to 70 countries and has spent 14 years teaching overseas, dragging her own children around with her. She enjoys writing about her travels, and has been runner up in our New Travel Writer of the Year Competition on three separate occasions.