In parts of the Cotswolds it is indeed impossible to do anything but go slow – narrow and contorted lanes wind their way up steep hillsides, and many villages seem decades away from the modern world.

Caroline Mills, author of Slow Travel The Cotswolds: the Bradt Guide

Did you know that there are more linear miles of drystone walls in the Cotswolds than make up the Great Wall of China? They’re only walls, you might say. But they’re special, unique and one of several features that help to make the Cotswolds look the way it does – fabulous!

The region continues to endear itself to anyone who visits – its harmonious combination of quintessentially English villages, charming provincial market towns, interesting and appealing countryside and a wealth of local food-and-drink producers makes it an all-year-round destination, whether for a day trip, a quiet weekend away or a multi-week holiday. The Cotswolds offer an incredible array of accommodation, from unique country-house hotels to delightful B&Bs on working farms, luxurious self-catering cottages to glamping and camping in secluded countryside.

Visitors with a particular passion or interest for gardens, the Arts & Crafts Movement, historic buildings, walking (miles of footpaths include the Cotswold Way National Trail), horseriding or rural pursuits are well provided for within the Cotswolds. Cyclists too, despite the Cotswolds’ many hills – if you’re not quite as fit as you’d like to be, you can always hire an electric bike to gain a little assistance.Combine your visit to the Cotswolds with a ‘city break’ in one of the gateway towns – Stratford-upon-Avon, Oxford or Bath – and you’ll be wanting to book your next visit before you’ve even left.

Bradt on Britain – our Slow Travel approach

Bradt’s coverage of Britain’s regions makes ‘Slow Travel’ its focus. To us, Slow Travel means ditching the tourist ticklists – deciding not to try to see ‘too much’ – and instead taking time to get properly under the skin of a special region. You don’t have to travel at a snail’s pace: you just have to allow yourself to savour the moment, appreciate the local differences that create a sense of place, and celebrate its food, people and traditions.

For more information, check out our guide to the Cotswolds

Food and drink in the Cotswolds

Savouring the tastes of the Cotswolds

There was a time when British food was considered lacklustre and dull, a poor relation to the gourmet cuisine of continental neighbours. Not so in the Cotswolds, whose farming traditions go back centuries. Pubs, restaurants and cafés are plentiful in the Cotswolds with many using the wealth of produce from the doorstep and, while there are still bland menus out there, I’d say that there are more places to eat with excellent food than there are with indifferent menus.

That’s, perhaps, not surprising given the enormous choice of local, seasonal and organic food that is produced in the Cotswolds – and which you can also get your hands on at a plentiful supply of farmers’ markets, organic farm shops or, indeed, by visiting the place where the food and drink is produced. Visit Winstones Icecream and you’ll just as likely see some of the cows sat outside the icecream parlour enjoying the same view of Stroud that you can; head to Cotswold Lavender during the summer and you can sample lavender shortbread while overlooking the purple hues; or take a tour of the relatively new Cotswolds Distillery and see how its gin is made – the barley used is taken from the surrounding fields.

If you like unique, you can purchase milk that pours from a tap at Nell’s Dairy or rare-breed beef from the National Trust’s Ebworth Estate whose cattle are kept deliberately to maintain the look of the Cotswolds. If it’s Cotswold lamb that you wish to taste, make sure that you check it is the meat of the actual Cotswold sheep rare breed and not simply meat from sheep grazed in the Cotswolds.

Savouring the tastes of Bath

Bath is one of the best places to visit in the Cotswolds and one of its big attractions is making the most of its remarkable selection of places to eat and drink. The city is one of the places in Britain that made drinking tea fashionable and there are plenty of options for experiencing a civilised afternoon tea. Beware, though, as many tea rooms are either closed or stop serving tea by 16.00 in preparation for dinner service. The city also has numerous very hospitable pubs and excellent restaurants. You won’t go hungry in Bath!

Tea rooms & cafés in Bath

The Bertinet Bakery: The Bertinet Bakery is a reputable artisan bakery in two locations producing breads, viennoiserie, pastries and savouries. Brunel Square also offers tea and coffee to take away while New Bond Street has the patisserie. Its world-renowned cookery school teaches novices how to make proper bread too.

The Green Rocket: The Green Rocket is a vegetarian café that also offers vegan and gluten-free options, along with organic coffee, freshly squeezed juices, wine and beer. Dishes include summer coconut and cashew curry, tomato, olive and baby spinach risotto and fresh linguine with porcini and tarragon cream sauce.

The Pump Room: The Pump Room is an attraction in its own right and was considered one of the most socially desirable places to ‘be seen’ for over 200 years. You will often find a queue for morning coffee, lunches and afternoon tea; book for dinner in the summer months. Come here to try the spa water and the distinctive Bath bun. Listen to the Pump Room Trio or the resident pianist perform while you eat.

Pubs & restaurants in Bath

Coeur de Lion: Promoted as ‘Bath’s smallest pub’, the Coeur de Lion is also on one of Bath’s narrowest, pedestrianised streets. With a long and celebrated history that includes much petition by locals to prevent the pub from being closed down in recent years, the Coeur de Lion is regularly included in CAMRA’s Top 100 British pubs. Oozing character (and people) – it really is small and boasts stained-glass windows and a long bar, but little else owing to its size. It is owned by one of Bath’s breweries, Abbey Ales.

Hall & Woodhouse: Owned by the famous Hall & Woodhouse Brewery (Badger Original, Fursty Ferret, Tanglefoot, etc), this is a very large and magnificent bar-cum-restaurant. It offers superb food and drink and attentive service, but visit for the surroundings alone – choose from several areas, each with its own ambience: by the entrance, a winter garden conservatory-style area with shelves filled like an old grocer’s store; to the rear, a large living room with sofas, coffee tables, rugs, a giant fireplace and bookshelf where you can help yourself to a book, copies of the Beano or a board game for the evening. Great with families and couples alike. Up the starlit staircase is a silver-panelled restaurant with glass chandeliers; you can watch the chefs at work here. Or head to the Manhattan-style rooftop terrace (open only occasionally) for views of the city. A place to take time and relax.

Pulteney Arms: Five minutes’ walk from Pulteney Bridge and Sydney Gardens, in a quiet residential area, the Pulteney Arms is this friendly pub with lots of character: exposed stone walls inside, together with period fireplaces and original gas lighting. There is a tiny rear terraced garden; guests also spill out onto the pavement, where additional tables and seating are provided. It is popular with the rugby crowd (Bath Rugby Ground is five minutes’ walk away). Good home-cooked food; try the seasonal ‘Taste of…’ menus, serving local, in-season produce.

Salamander: Salamander is an unpretentious ‘black-and-gold’ town centre pub owned by Bath’s brewery, Bath Ales. On the ground floor is the blackened-wood bar area (wooden bar and shelves, wood floorboards, wood bar stools) and upstairs is the supper room. Bath Ales are obviously the main tack to accompany the menu (pies with gravy and mash or light bites).

Sally Lunn’s: This is a Bath institution. While Sally Lunn’s is celebrated as a place for morning coffee and afternoon tea, it’s less known for its quiet candlelit dinners, and yet I’ve eaten extremely well here. In the quaint old terraced tea shop, full of ambience and friendly staff, you’ll find very good, hearty food. Try the ‘trencher’ meals, served on the famous Sally Lunn Bun, a brioche-like bun from the 17th century; meat and gravy on a bun may not sound right but it really works. This is the only place in the world to buy the Sally Lunn Bun.

Where to stay in the Cotswolds

For information about accommodation, see our list of the best places to stay in the Cotswolds.

What to see and do in the Cotswolds

Bath

Could we imagine being without Bath? England, Britain, the World would be significantly poorer if it had never been created, for Bath has culturally enriched our lives over the centuries. That’s why the city is classified by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, a status that it shares with the Taj Mahal, the Pyramids of Giza and the Great Wall of China, for providing ‘outstanding universal value to the whole of humanity’.

Four Shires

This is the hidden part of the Cotswolds, the forgotten part, the part that the coach tours leave out – and it is all the better for it. Not as dramatic as the western escarpment, it’s cosier and has just three small towns in the west – Shipston-on-Stour, Moreton-in-Marsh and one of the most rural, Chipping Norton.

Strictly speaking, there are only three shires within this chapter – Warwickshire and Oxfordshire, plus a tiny scrap of Gloucestershire. The ‘four shires’ refers to the Four Shires Stone, not far from Moreton-in-Marsh. It marks the point where four counties once met – Warwickshire, Oxfordshire, Gloucestershire and Worcestershire. The borders have changed and now Worcestershire begins several miles away. Within these boundaries, the areas become even more localised. We’re at the very southern tip of Warwickshire, and the most northern part of Oxfordshire. Residents in these borderlands will feel much more akin to one another than they will to the remaining parts of their respective counties. Even the term ‘Banburyshire’ (referring to the market town of Banbury just east of this locale) is still used today, demonstrating the closeness of the two counties at this point.

The bond between south Warwickshire and north Oxfordshire is perhaps because of their shared heritage and style of architecture. This is still the Cotswolds – just. We are on the very fringe here and, though there are still plenty of rolling hills, it is the flattest part of the Cotswolds overall, leaving the sharp western escarpment behind.

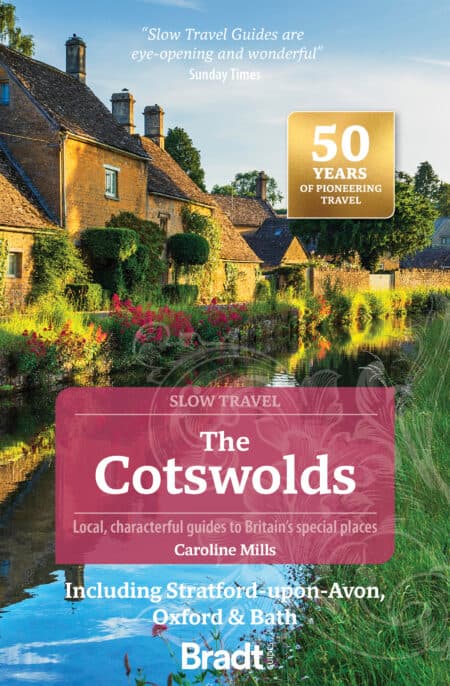

The eponymous water that flows through Bourton-on-the-Water © Caron Badkin, Shutterstock

High Cotswolds

There’s a little bit of everything in this area. In the east, the curvy hills remain with interlocking valleys and vistas that make you feel a part of the landscape. Some of the most visited villages and towns are here: the Swells, the terrifying-sounding Slaughters and the hyphenated beauties of Stow-on-the-Wold and Bourton-on-the-Water. I’ve also slipped in some lesser-known jewels that rarely make it onto the tourist trail itinerary, such as Salperton and Longborough, Kineton and Hampnett.

In the north, the town of Winchcombe has established itself as a base for walkers and is proud of its image as a working tourist town without the trappings of being ‘too pretty’.

Further west, you begin to see the more aggressive side to the Cotswold Hills, rugged escarpments that on a windy day make walking on the edge feel somewhat threatening. Places such as Cleeve Common, the highest point in the Cotswolds, and Leckhampton Hill – alternately sublimely calm or alarmingly volatile when a storm approaches and the air is thick with deep mauve thunderclouds.

These hills envelop the spa town of Cheltenham, struggling to cling onto the glory days of its former life as a fashionable health resort yet still retaining that charisma in places.

My heart lies somewhere between them all – the high points in the west and those mellower pastures in the east, striped with flourishing hedgerows and guarded by stone walls, standing defiant whatever the weather throws at them.

North Cotswolds

This covers the northwest tip of the Cotswolds, the very fringes where the rocks and the stone peter out – or begin. Within my locale’s entirely hand-drawn boundaries lie five very distinct and different areas – the northern fringe of villages running along the River Stour in south Warwickshire and the tiny part of the Cotswolds that flows into Worcestershire around the Vale of Evesham and Bredon Hill, all of which frame the start of the Cotswolds AONB near the Hidcotes and Chipping Campden. Further south, more familiar names start to crop up such as Broadway and Snowshill, by which time we are well and truly immersed into the Cotswolds. This is bolt-hole territory for me, just a few miles from home and where I can spend a few hours enjoying a view or taking a walk; Ilmington Downs and Dover’s Hill will always be special simply for their views, but I love the simplicity of an off-thebeaten-track walk in the Stour Valley too.

Oxford

It was the poet Matthew Arnold who first described Oxford as the ‘city of dreaming spires’ in 1865, and the epithet has stuck ever since. Arnold was a professor of poetry at the university when he penned it, depicting the panorama of turrets and pinnacles seen from Boars Hill, southwest of the city. Seen from here or any one of the other viewpoints around the outskirts of the city, or by climbing a tower in the centre, the skyline has a magical quality that makes even the most hurried tourist stand still for a moment. It’s like seeing the Duomo in Florence for the first time or the plan of Paris from the Arc de Triomphe.

Stratford-upon-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon. What more is there to say about this town? As the birthplace of Shakespeare, it has been written about for centuries, ’done’ by coachloads of ocean-hopping sightseers on wearying whistle-stop tours of Britain, and is arguably more famous than capital cities ten times its size. And yet, despite it being so celebrated, how many visitors actually get to know Stratford?

Thames Valley

Where do you immediately think of as the Thames Valley? Reading, Goring, Marlow or Windsor, perhaps? The phrase has been usurped to represent a particular region between Oxford and London for politics, policy and organisation. How about Kemble, Cerney Wick or Inglesham? The true Thames Valley begins in rural Gloucestershire, 53 miles west of Oxford.

It’s hard to imagine the source of the Thames being anywhere other than where it actually is, but the debate over its location has divided opinion for many years and was even discussed in the House of Commons in 1937. Officially, the Thames Head is close to the Fosse Way between the villages of Coates and Kemble, a mile south of Cirencester. It remains dry for most of the year – I’ve never seen it so much as trickle from the ground here in many years – while the source of the River Churn, at Seven Springs southeast of Cheltenham, could actually be the Thames’s true source. It never dries up and, being longer to the confluence than the Thames, should theoretically be the main river.

It would be a brave soul to suggest change either to its route or its name now. The Thames is a part of the British psyche. From the river’s gentlest of beginnings, it seeps through the village of Ewen before winding through the old gravel pits that more recently have become the Cotswold Water Park. It soon gains water and is most definitely a reasonable stream when it reaches the edge of Cricklade, the first town on its journey. From there the river passes through flat open countryside with few villages to get in its way as if with a burning desire to become larger, fuller and more self-confident once the tributaries of the Coln and the Leach add to its stature. By the time it passes through Lechlade-on-Thames, the first town to bear its name, the river is navigable. Small marinas appear and the first of the locks, St John’s Lock, is just east of the town where the reclining figure of Old Father Thames proudly watches over his adolescent child. Both Cricklade and Lechlade are Cotswold gems that often get overlooked by tourists concentrating on the big-name towns.

Within a few miles the river has all but left its Cotswold roots behind, passing through open vales rather than a valley lined with hills. Only when it comes close to Oxford does it show any signs of being a Cotswold river again, passing by suitably Cotswoldesque architecture, but by now the river has grown up, left its youthful home behind and continues its 215-mile journey to the North Sea as an adult responsible for grownup boats and beautifying the grounds of dazzling, upmarket riverside properties. This chapter focuses solely on its youthful beginnings, until just east of Lechlade, when the river passes by the Buscot Estate and Kelmscott Manor, the home of William Morris.

The Southern Cotswold Scarp & Five Valleys

While the northern and eastern areas of the Cotswolds are cosy, gentle and lay claim to soft undulations, the southern Cotswolds are rugged, raw and wild. Sharp escarpments and gorge-like river valleys twist and bend with absurd frequency, funnelling cold winds and trapping fog. In between the contorted valleys and giant beech woods, high ground amasses creating rough commons, superb for bracing walks and views.

There’s an edgier feel to the area too. Where the softer wolds of the northern Cotswolds belie their rural heritage of rearing sheep and selling wool with the odd farmstead and squire’s manor house dotted across the countryside, here is the corresponding industrial landscape. Cloth mills, originally powered by the area’s fast-running waters, lined the valley floors and the steep escarpments meant that builders had nowhere to go but up. Consequently, the houses of the workforce cling limpet-like to the valley sides.

Having skirted around Cheltenham, the western escarpment continues to run south from Crickley Hill towards Stroud and then on towards Dursley until it reaches the graceful city of Bath. This section of the escarpment has some of the most dramatic views in the Cotswolds, over the Severn Valley and into Wales.

In the hinterland, the area around Stroud is known as the Five Valleys. Synonymous with the cloth industry, each of the five valleys follows small streams; to the east there are further valleys, unconnected to the cloth industry, that are completely dry. There are no giant rivers here. North of Stroud is the Painswick Valley, its western ridge making up a part of the main Cotswold escarpment. Northeast is the Slad Valley, made famous by the author Laurie Lee, who lived there for much of his life.

To the east is the Frome Valley, otherwise known as Golden Valley when it edges ever closer towards Stroud and, like a northerly spur from it, the Toadsmoor Valley. Running due south of Stroud is the Nailsworth Valley. At first it is as steep as its neighbours but gradually the land begins to flatten and the odd barbed spur escapes, such as at Woodchester to the west and towards Avening and Tetbury to the east.

The area of the Five Valleys is unique in Britain. The whole landscape is bizarre and intriguing. I love visiting – and yet I’m glad to escape to the high ground of Minchinhampton and Rodborough commons or to stand on top of the escarpment and breathe in great gulps of air.

The Thames Tributaries

It might seem bizarre to be referring to both the Cotswolds and the River Thames within the same sentence, as the Thames Valley, London and Thames Estuary seem a different world. But the source of the Thames bubbles out of the Cotswold hills and a large swathe of the Cotswolds lies north of the Thames, within which are five small river valleys – the Churn, Coln, Leach, Windrush and Evenlode – each a tributary of Britain’s most famous river.

Not one of the rivers here is particularly well known, but the villages and towns that they flow through are more acclaimed, such as Cirencester on the Churn, or Burford on the Windrush or the village of Bibury on the Coln. Yet each river valley very much has its own individual character.

Two counties fall into this area – Gloucestershire and a large chunk of Oxfordshire. Often referred to as the Oxfordshire Cotswolds, this is an area of the Cotswolds that is occasionally forgotten about when so much emphasis is placed upon the western escarpment.

Wiltshire Cotswolds

For some, Wiltshire is more associated with Salisbury Plain and the Vale of the White Horse than the Cotswolds, but a reasonable chunk of the Cotswolds does fall into the county. Because the area is less known, its quiet, untouristy nature gives quite a sense of discovery.

Towns such as Malmesbury, Corsham and Bradford-on-Avon all have their own character and just a day spent in each should leave you feeling that you’d like to spend longer. But it’s the countryside that is the jewel here, much of it appealingly remote. In the north of this locale, above the M4, the land lends itself to open wolds – Malmesbury sits on top of one of them. But below the M4 corridor the land begins to twist and turn again, providing sharp ridges and secret valleys around the edge of Bath.

One of the best valleys for exploring is By Brook. In the north, close to its source, it is relatively well known and tourist orientated, including Castle Combe, one of the great showpieces of the Cotswolds. But further south it uncovers equally worthwhile villages such as Ford and Slaughterford, with plenty of opportunities for walks off the beaten track.

I’ve sneaked north Somerset and a tiny snippet of Gloucestershire into this locale too, for the ridges of hills know no authoritative boundaries, and secrets such as St Catherine’s, which lies within ten yards of the Wiltshire boundary, are too good to miss by being overly picky about where the dotted line falls.

I met a man who had been stationed at one of the barracks in the area while performing his National Service in the 1950s. He reminded me of the important role that the military has played here over many years – there are still several military bases and operational units in the area. He told how, on a Friday evening, the roads for miles around, in particular the London road (now the A4 between Bath and Chippenham) out of Bath, were lined with personnel trying to thumb a lift to go home for the weekend.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to the Cotswolds:

Related articles

From medieval castles to Edwardian Arts-and-Crafts architecture.

Far more than just the home of Shakespeare, Stratford-upon-Avon is the perfect choice for anyone seeking a classic English getaway.

Take it slow and savour these pockets of tranquility.

Ideal for picking up some produce for a picnic or a family day out.

These are some of our favourite green spaces to wander in England.

Some people go to church, others go to churches.

There are many places and features around Oxford that crop up in Lewis Carroll’s books.